Working paper 3: Preliminary analysis of policy differences across the four UK jurisdictions

All Media All Locations July 6 2021

Working Paper 3: Preliminary analysis of policy differences across the four UK jurisdictions

Professor Ewen Speed, School of Health and Social Care, University of Essex

Click here to download the PDF version of the working paper

1. Introduction

This working paper describes the development of an initial policy analysis framework for comparative analysis of the voluntary response across the 4 UK jurisdictions. It is intended as a discussion document for the different UK voluntary action research teams.

The paper is prepared by Ewen Speed for the ESRC/UKRI funded project “Mobilising Voluntary Action in the four UK jurisdictions: Learning from today, prepared for tomorrow.” It is the third in a series of working papers reporting from the various work strands of this rapid response project addressing recovery from pandemic. This working paper reports a single part of work strand ‘B1’, policy documents, months 2 – 11. Strand B1 is directly concerned with collating data and providing analysis to address research question 1: In what ways do the voluntary action policy frameworks adopted by the four nations in response to COVID-19 differ? And how effective are they?

This working paper summarises the analytical work in delineating the different policy frameworks across the 4 jurisdictions to gain an informed understanding of similarities and differences in the ‘voluntary action’ policy contexts across the UK.

2. Rationale for Strand B1

In order to address the research questions underpinning strand B1 it is necessary to undertake a number of preliminary activities to frame the analysis. First, there is need to outline the operational definition of what constitutes a policy framework. In order to accomplish this, this report will first establish points of similarity and difference across the four jurisdictions in relation to voluntary action. Comparative analysis of the jurisdictions will facilitate the delineation of distinct policy frames for each jurisdiction, characterising points of concurrence and divergence between the different constituencies.

Within the context of the overall United Kingdom, there would be the expectation of some degree of policy congruence, because of the political union of the 4 jurisdictions (in effect the UK features here as a fifth jurisdiction, with dominion over the other 4 devolved jurisdictions). However, since the late 1990’s, following the three acts of devolution across Northern Ireland (Belfast Agreement 1998), Scotland (Scotland Act 1998) and Wales (Government of Wales Act 1998) there has been some divergence in policy. Devolution operates on a central principle of division between reserved and devolved matters. Those matters that are reserved remain under the purview of the UK government, for example, issues such as tax raising powers and defence. Those matters that are devolved are under the purview of the respective devolved assembly or parliament, such as the provision of health and social care. For example, across the 4 UK jurisdictions there are very clear differences in how the National Health Service (NHS) provides and delivers universal healthcare, and these modes of provision and delivery have changed markedly since devolution. This temporal component to the policy documents is crucial, particularly in the context of accelerated health and social care policy making in the time of the pandemic. Many of the policy contexts in which voluntary action is legislated for are in the field of devolved matters, that is to say, they are not under the purview of the UK government. As such, there is a clear rationale to expect there to be policy differences across the 4 jurisdictions.

Working with voluntary action collaborators across the 4 jurisdictions, a series of workshops took place to develop shared understanding of the policy analysis component of the project. Specific policy researchers were identified within each jurisdiction to contribute to discussions around the development of distinct policy frameworks and to source and collate relevant policy documents from respective governments (parliamentary debates, scrutiny committees etc), and grey literature, such as press releases and webpages from voluntary organisations). Discussion about the relevant time period for the respective legislatures was a prominent feature of these discussions. For example, there was a protracted period between 2017 and 2020 where the devolved Northern Irish assembly was not sitting due to inability to form a workable coalition. This had a very direct and immediate impact on policy making in that jurisdiction.

The contents of this report represent the initial discourse analysis of these policy documents. The approach enables the specific characteristics of each policy framework to be delineated individually, before the second stage of the analysis then brings these specific characteristics to bear upon in other in comparative analysis. This component of the overall project is concerned with establishing the nature of the policy framework differences between the 4 jurisdictions and utilising this as a vehicle for discussion in terms of how these differences may have impacted (positively and negatively) upon the mobilisation of the voluntary response in the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Methodology for Strand B1

The analysis utilises a logics of critical explanation approach (Glynos and Howarth, 2007) which is in turn influenced by discourse analytic techniques. It involves a two stage analytical process. Firstly, analysis of landmark policy documents (identified by the policy researchers) to establish the dominant ways of framing voluntary action that prevail across the different jurisdictions, in a within-case analytical frame (e.g. the English case, the Northern Irish case, the Scottish case and the Welsh case). Secondly, comparative analysis across these different jurisdictions in a between-case analysis to identify points of concurrence and departure, with a view to exploring how the jurisdictional differences impacted upon the voluntary action response to the pandemic.

Discourse analysis is principally a concern with establishing how specific entities (e.g. a national government, or a regional organisation or local residents association) construct their understanding of social constructs. These social constructs are oftentimes abstract. The idea of community volunteering is a useful example to explain this point. Whilst everyone knows what community is, and everyone knows what volunteering is, efforts to understand how people think about and make sense of the idea of community volunteering differ hugely from person to person and country to country. There are clear influences in how we make sense of the idea of community that are shaped by local, national, political, cultural, economic to name but a few. In order to understand how discourses of community volunteering are constructed within any particular context, there is a need for the analyst to collect relevant documents from specific contexts and to analyse the dominant (and the marginalised) ways of speaking about that specific abstract concept in that context. The assumption is that some of those differences, enacted through respective acts of parliamentary devolution, will become evident in the ways that the respective assemblies develop legislative policy in relation to community volunteering. To be clear, the processes of discourse analysis are fluid and dynamic, the intention is not to arrive at a fixed definition of Northern Irish, Scottish, or Welsh voluntary action, but rather to explore how processes of differences and similarity might be playing out across these different policy contexts.

3.1 Methodological note

In separating the English case out from the other jurisdictions, a difficulty emerges in that there is no devolved English assembly. As such, disaggregating English voluntary action policy from UK policy, and then in turn further disaggregating it from Northern Irish, Scottish or Welsh policy becomes a difficult task[i]. This is primarily because there is no locus where we might look to source English volunteering policy. Indeed, it is a paradox of UK government that there is no explicit English policy agenda for many areas of government. There are obviously explicit policies for some issues such as health and social care, but other issues, which perhaps are seen to be of lesser priority, operate in a liminal context whereby the devolved policy programme of a respective jurisdiction tends to be developed and implemented in relief against the non-reserved UK policy (which could be more accurately described as English policy, but there is no devolved English assembly or parliament to consider it as English policy). Somewhat incredibly, it is possible for this contradiction to persist without provoking a constitutional crisis, largely because the UK does not have an explicit constitution(!). This effect might be best characterised as a ‘paradox of English Exceptionalism’.

To further complicate these distinctions, there is no extant voluntary action strategy which is being currently applied to England. The most recent UK policy wide push for engagement in terms of voluntary action goes back to the Big Society policy programme from 2009/2010 (Woodhouse, 2015). The Big Society policy programme was predicated upon the idea of ‘social value’ (Dowling and Harvie, 2014), where this is broadly defined as the positive non-financial impacts and outcomes of programmes, organisations and interventions. In this context, social value is used to “quantify the extent that particular initiatives contribute to a better functioning, socially cohesive and environmentally sustainable society,” (p.880, ibid.).

As such, social value provides an important framing context for the analysis that follows. It is a hypothesis that the four jurisdictions have developed quite different operational definitions of the ‘social value’ of voluntary action and that this has impacted significantly upon the differentiated development of voluntary action policy and practice across these jurisdictions.

The analysis will now consider each country in turn, organised in terms of the chronology of the date of publication of their respective voluntary action strategies, taking a consideration of how they codify social value differently as a within-case point of departure for the analysis.

4. Preliminary Analyses of the Four Jurisdictions

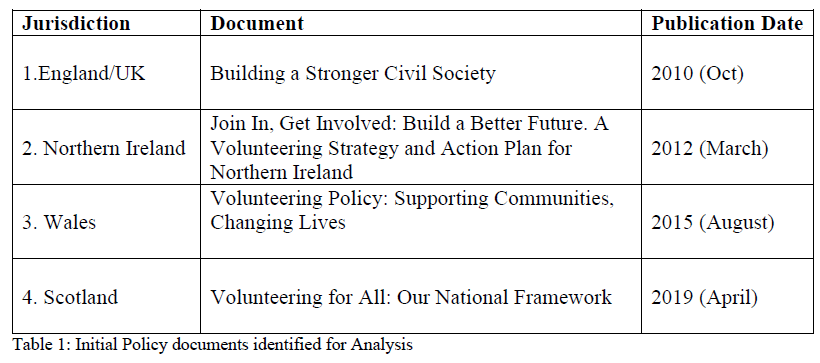

The analysis of 4 jurisdiction policy documents that follows is organised around the different geographical jurisdictions and commences with the agreed initial policy framework documents. These documents were selected as the most recent voluntary action strategy documents issued in the respective jurisdictions, at a point closest to the initial UK pandemic lockdown on 23rd March 2020. The selected initial policy documents are presented in table 1.

4.1 Within Case Analysis

4.1.1. England: Building a Stronger Civil Society (2010a) Cabinet Office, pp.13.

The document ‘Building a Stronger Civil Society’ (2010a) stipulates three core components for building a stronger civil society. It was an agenda setting document for the ‘Big Society’ policy programme, (Woodhouse, 2015), which was championed by then Prime Minister David Cameron, and proposed

“redistributing power from the state to society; from the centre to local communities, giving people the opportunity to take more control over their lives, [in order to develop a…] a society with much higher levels of personal, professional, civic and corporate responsibility; a society where people come together to solve problems and improve life for themselves and their communities; a society where the leading force for progress is social responsibility, not state control.” (The Cabinet Office, 2010b).

Much of the ‘big society’ policy impetus was subsumed under a nascent localism agenda, and there was a general lack of consensus about what ‘the big society’ actually was.

The document ‘Building a Stronger Civil Society’ stipulates three core components for building a stronger civil society. Only one of these touches explicitly upon voluntary action (point 3). However, there is clear scope of voluntary action across all three components.

- Empowering communities: giving local councils and neighbourhoods more power to take decisions and shape their area.

- Opening up public services: the Government’s public service reforms will enable charities, social enterprises, private companies and employee-owned co-operatives to compete to offer people high quality services;

- Promoting social action: encouraging and enabling people from all walks of life to play a more active part in society, and promoting more volunteering and philanthropy. (p.3).

All three of these components are intended to create new opportunities for the ‘voluntary and community sector’ to shape and ‘provide innovative, bottom-up services where expensive state provision has failed,’ (p.3).

By implication, this new provision will be local and inexpensive, with the commissioning and provisioning of public provision at a local level expected to be more effective and efficient. A drive towards localism underpinned much of the austerity led policy context in the UK between 2010-2015. For example, many councils were encouraged to become enablers rather than providers of local services (Yeandle, 2016). This then overlaps with component two, which can be read as a push for a reduction of statutory provision, to be replaced by third sector and private sector contracting (which in turn would be constrained by the need to demonstrate social value). In terms of the third point, promoting social action, the document outlines a commitment to “Creating a society where taking an active role in society is both expected and rewarded will also benefit voluntary and community sector organisations by encouraging people to give their time, their expertise and their money.” This societal shift is predicated upon an expansion of firstly, citizen action (e.g. encouraging people to think about the contribution that they make now and how that might change) and secondly, community action (e.g. identifying and training 5000 new community organisers).

Much of the strategy is vague and undefined. There is little mention of engagement with existing voluntary action organisations at local or national levels. The focus of the document is very much on pressing new citizens into voluntary action roles. Dominant tropes within the document focus on a nebulous and amorphous voluntary and community sector (which is never defined), coupled to repeated claims about the need for reduced government and increased activity at local level, with new opportunities for public and civil society actors. It is couched within a transactional mode of exchange between the state and individual citizens, where citizens are volunteering activities that were previously offered by the state. There is a little attempt to engage existing voluntary action organisations in this activity, the appeal is made directly to citizen actors, to engage in voluntary action which facilitates a retraction of the state.

4.1.2. Northern Ireland: Build a Better Future: A Volunteering Strategy and Action Plan for Northern Ireland (2012), Department for Social Development, pp.36.

The document for Northern Ireland (DSDNI, 2012) was identified as an explicit Volunteering Strategy. It was produced two years after the English/UK document. There is no mention of a nebulous Voluntary and Community Sector, rather the emphasis is on collaboration with existing volunteering organisations within the community. The emphasis is very much on engaging and developing existing activity. For example, in offering the context for the strategy, the document outlines the strong history and ethos of volunteering in Northern Ireland (p.13). The context offers a review of existing voluntary action (e.g. citing 280,00 regular NI volunteers) and outlines the consultation process that led to the creation of the strategy. It cites the devolved Executive’s vision for volunteering in Northern Ireland, as a society where “everyone values the vital contribution that volunteers make to community wellbeing,” and where “everyone has the opportunity to have a meaningful, enjoyable volunteering experience.”. This is predicated in principles of fairness and equity, free will/choice and mutual benefit. Choice in this invoked in this strategy as a principle of democratic participation. In the English context, choice has tended to be mobilised in policy as an instrument of individualised transactional choice (Glynos, Speed and West, 2014). Reference is also made to the mutual benefit of volunteering, characterised as shared experience, which extends social networks.

The Northern Irish strategy sets out to gauge, enhance and develop existing voluntary action provision, across five action plan areas

- Recognising the value and promoting the benefits

- Enhancing accessibility and diversity

- Improving the experience

- Supporting and strengthening the infrastructure

- Delivering the strategy

Across the entire document, there is a clear investment in principles of diversity, particularly in recognition of the need to acknowledge the voluntary action work that many faith-based organisations offer. The point we make here is that not only does the strategy identify the range of different citizens contributing to voluntary action, it also proposes specific strands of strategy to engage with specific categories of volunteers. This is a marked difference to the amorphous citizens in the English document. Furthermore, much of this strategy is not about retracting the state, but rather in seeking to identify ways in which the state can work in partnership with a diverse range of voluntary action actors to increase and improve the range and number of opportunities for people to engage in voluntary action across all sectors of Northern Irish society, in effect identifying and embedding a supportive state role in ongoing development of voluntary action in Northern Ireland.(Cabinet Office, 2010a)

4.1.3. Wales: Volunteering Policy: Supporting Communities, Changing Lives (2015) Welsh Government, pp.20.

In common with the Northern Irish strategy, this Welsh Government (2015) document makes a very explicit commitment to supporting volunteering, which is characterised as an “important expression of citizenship and as an essential component of democracy,” (p.3). The policy document stipulates three criteria. It is intended to:

The purpose of this policy is to:

- improve access to volunteering for people of all ages and from all parts

of society;

- encourage the more effective involvement of volunteers, including through

appropriate training;

- raise the status and improve the image of volunteering

As with the Northern Irish document, the emphasis is very much on developing the ongoing voluntary activity in Wales, including an express commitment to ‘ensuring that paid staff should not be removed in order to directly replaced them with volunteers,’ (p.4).

Similarly, emphasis is also placed on ensuring parity of access to voluntary action in terms of diversity (with a specific emphasis on age). The document then sets out a programme of action for implementing these policies across the Welsh government, volunteer involving organisations and third sector infrastructure (e.g. ongoing support for a national Welsh online voluntary action portal). In terms of questions of social value, Annex B of the policy document outlines a range of benefits of volunteering, across individuals, organisations, and the wider community. There are four listed benefits for the wider community, at both individual and social levels. For example, individual benefits are attributed to ways in which ‘active voluntary involvement can improve well-being across aspects. Social benefits are argued to accrue for voluntary involvement in service provision (such as police service volunteers freeing up officers to perform key operational duties), which helps ‘to develop a strong civil society and resilient and vibrant communities,’ (p.15). Reference is also made to principles of democratic participation, with volunteering described as an ‘expression of democracy – people exercising their right to associate and act for change’. Clear lines of accountability are stated between third sector organisations and government. Lastly, reference is made to increased levels of inclusion and social cohesion, in terms questions of accessibility across a range of potentially marginalised groups, where volunteering ‘can provide opportunities to foster understanding and friendship between factions within the community and to combat isolation and prejudice,’ (p.16). Across these criteria there is a clear commitment to a very positive framing of the social value of volunteering, where is regarded as something that adds positive value to a range of relations and engagements across individuals, communities and wider society, where voluntary action is works in tandem with, and is supported by the state. The strategy is very clear in constituting who the range of relevant actors are, and in attributing a programme of activities for those different actors, across a clearly defined field of voluntary action.

4.1.4. Scotland: Volunteering for All: Our National Framework, (2019) Scottish Government, pp.40.

Very much in line with the other devolved jurisdictions, the Scottish Government (2019) document makes a very clear commitment to the social value of volunteering. The document stipulates four primary objectives for the Scottish government and Scottish society in terms of voluntary action. These are:

- Set out clearly and in one place a coherent and compelling narrative for volunteering;

- Define the key outcomes desired for volunteering in Scotland over the next ten years;

- Identify the key data and evidence that will inform, indicate and drive performance at a national and local level;

- Enable informed debate and decision about the optimal combination of programmes, investments and interventions.

The framework provides an overview of existing voluntary action, pointing out where there is need for improvement (e.g. 19% of all volunteers provide 65% of volunteering hours). This evidence-based focus plays out across the framework. The document also very explicitly identifies the relevant seven stakeholder groups that constitute the voluntary action field in Scotland. These are identified as the Scottish Government, NHS and Social Care, Business and employers, Volunteer Involving Organisations, Funders, Local Authorities and Leadership Bodies across the third sector (p.8). There is a strong emphasis placed on the social value of voluntary action, for example, a sum of £2.26bn is given as the value of voluntary action to the Scottish economy. This figure is reported alongside claims about the value of voluntary action in terms of physical health, social benefits, mental well-being and instrumental benefits (such as increased employability). Throughout the document there is a clear commitment to evidence based policy making, as claims and objectives are linked to a range of evidence sources and case studies which serve as exemplars for the social value of voluntary action across the seven identified stakeholder groups.

The framework also outlines a typology of volunteering, identifying a dimension of involvement from neighbourliness on one end to formal volunteering at the other. This demonstrates a different type of engagement with ideas of voluntary action in terms of policy making, and suggests the Scottish Government has a desire to think about voluntary action in a more nuanced way.

There is an emphasis within the document to speak to the audience as citizens who might also volunteer. There is less emphasis on existing voluntary action. This is not to say that existing activity is ignored by the framework, it is not, it is in fact very much a feature of the framework. However, the document addresses more directly the ways in which people engaging in voluntary action will bring a range of benefits both in terms of voluntary action outcomes and in terms of national outcomes (see diagram on p.30).

The framework makes a very direct and explicit link between increased voluntary action and a successful country, with a range of opportunity for a diverse population, with ‘increased wellbeing, and sustainable and inclusive economic growth’, (p.30). This is predicated upon a stated government commitment to ensuring a country ‘where everyone can volunteer, more often and throughout their lives’, underpinned by six principles, concerned with ensuring a flexible and responsive field of voluntary action, where volunteers feel supported and enabled, where volunteering is valued, where is both meaningful and purposeful, in ways which recognise diversity and where the experience is sociable and connects volunteers with other people in the community and wider society.

The document then details a range of outcomes that the seven identified stakeholder groups should be expected to engage in to ensure the implementation of this framework. In effect the framework offers a detailed roadmap towards the development of a state-led framework for voluntary action, which combines the application of voluntary action across statutory provision and the third sector, by developing and supporting voluntary action across a range of stakeholders. Rather than focussing on specific voluntary action organisations per se, the framework focuses more on the development and support of volunteering opportunities across a range of actors. The emphasis is primarily on increasing opportunity for voluntary action across society.

4.2 Summary of within case analysis.

Considering each jurisdiction individually, there are clearly a number of specific features of each jurisdiction in terms of how it constitutes the field of voluntary action. The function of the within-cases analysis is to set out the parameters of each jurisdiction independently of the other jurisdictions. The preceding analysis does this by presenting an analysis of the respective policy regimes within the field of voluntary action in each jurisdiction. The analysis of these four ‘current’ voluntary action strategies are offered here as indicative statements of the ‘state of the art’ in terms of voluntary action across the four jurisdictions. There are of course methodological difficulties in comparing an elaborated strategy document published in 2019 with a agenda setting document from 2010. For example, the analysis of the English case does not take account of the 2020 report Levelling up our communities: proposals for a new social covenant, (the so-called Kruger review, Kruger, 2020). The Northern Irish analysis does not take account of the stasis that paralysed devolved government in Northern Ireland, where the Northern Irish Assembly did not sit between January 2017 and January 2020. These documents and developments are significant and influential in terms of the voluntary action policy field and will be considered in Strand B1 policy analysis WP2. It is important to bear in mind that when taking a discursive approach, the analytical emphasis is placed on understanding the different systems of sense making (Howarth, 2000). These systems of sense making are not things that simply exist, they are systems which have a genealogy and an archaeology. In order to understand the policy context of the present, there is a need to first establish how that present context has manifested, and that is the purpose of this working paper (WP1).

To return to the current analyses, the between cases analysis which follows will identify points of concurrence and departure in terms of these four jurisdictions in order to begin to sketch out a framework for identifying the key similarities and difference in terms of voluntary action responses to the pandemic..

4.3 Between-cases analysis

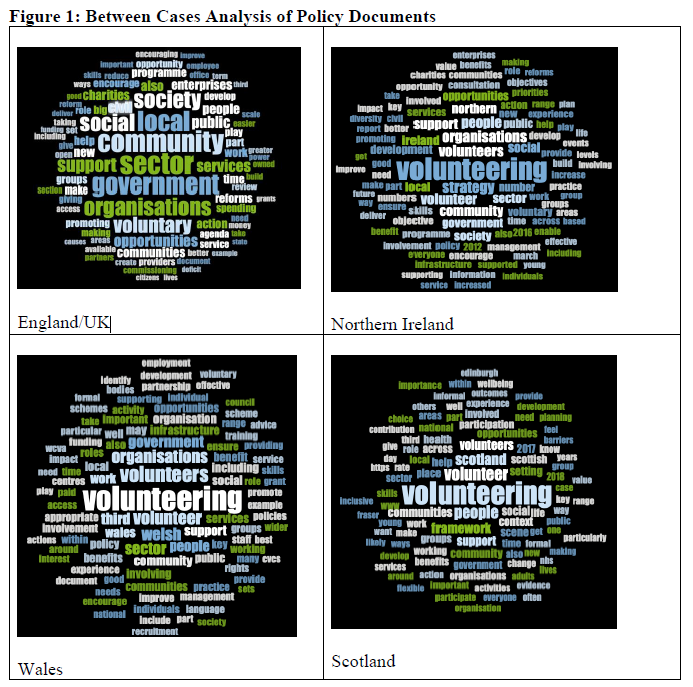

The initial review of policy documents indicated a divergence in terms of the English approach to volunteering. All other jurisdictions had produced documents which could be categorised as documents which explicitly outline volunteering policy. Figure One (overleaf) presents a visual representation of a frequency count analysis the four respective documents. The word clouds demonstrate quite clear a concurrence across Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland in terms of tropes around of volunteering, community and such like, and a clear divergence from the English document

Figure one demonstrates a frequency analysis of the four documents considered for this working paper. The larger words are the words which were mentioned more frequently in the respective documents. There is remarkable concurrence across Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland in terms of the focus on volunteering, whereas the English/UK document seemed to reflect more tropes around government, organisations and community.

It is also worthy of note that the documents from the three devolved jurisdictions, the respective nations all appear with some frequency, whereas this is not the case in the English/UK document. This would support the analysis of ‘English policy’ as an empty signifier.

In terms of the 4 documents, there is a clear divergence in how social value is defined (and indeed the inherent value of social value) and how it is operationalised across the voluntary action field. In the English document, social value is articulated as a financial metric, whereby voluntary action presents an opportunity for civil society to fill the vacuum created by a receding state.

This particular characterisation of social value tends to be predicated upon a very transactional model of civil society. The other jurisdictions all tend to define their framework against this orthodoxy, all variously making claims for need to emphasise a non-transactional model of voluntary action, one predicated on mutual benefit and exchange, and one in which the state is centrally involved, either an opportunity broker (Scotland) or as a contributing and directing partnership organisation (NI and Wales).

The paradox of English exceptionalism functions to fix English policy as a signifier, a slippery and nebulous policy context, which defies definition, which the devolved assemblies seek to define their policy against.

English policy, in the context of the other jurisdictions operates by acquiring different meanings and normative inflections depending on the context in which it appears and is drawn upon by the other jurisdictions. The lack of specificity in the English policy (marked as UK policy) ensures that the devolved jurisdictions must, to a degree define their voluntary action the English/UK government position. It must, by definition, be seen to be different from the English policy, but obviously this becomes difficult to maintain when there is no (explicit) English policy.

This paradox functions to maintain a position of continued hegemony for the English case in relation to the other jurisdictions. As such, the paradox of English exceptionalism can be read as a logic of difference, (De Cleen, Glynos and Mondon, 2018), i.e. as a set of practices which operate in ways that maintain (rather than challenging) existing structures, (e.g. the dominance of the UK parliament, over the regional assemblies and parliaments). The logic of difference operates to break up any potential alliances between different actors. For example, by refusing to define what the English policy context is, it becomes difficult for the other jurisdictions to join forces and align against it. Up until the COVID-19 pandemic, the case could be made that, in this context, the social demands and identities of the different jurisdictions were managed in ways that did not ‘disturb or modify a dominant … regime in a fundamental way’ (Howarth 2010 p. 321). The rejection of the Scottish Independence referendum in 2014 could be read as evidence for the success of this logic of difference. What COVID-19 has done, with the need for fast policy in terms of the public health response, has been to bring into stark relief what English policy is, for the other jurisdictions to see and for them to define and develop their policy against. In this context we see very clearly why there might be so much resistance to stating the English policy context, from the perspective of English politicians.

Furthermore, within this logic of difference an emphasis is placed on policies developed with the intention of undermining any ‘challenges to the status quo…’ and this tends to be accomplished ‘by addressing some (or all) of the concerns expressed by various groups or subjects, thereby preventing the linking together of demands’ (ibid p. 321). This is notable in the current context that the governments in the respective jurisdictions have been largely unable to develop any shared platforms of government, all pandemic policy everything tends to be constituted via a two-way relation between respective assemblies and London government (periphery to centre). In terms of developing the logic of difference position it might be useful to extrapolate these processes out to a wider context of meta-governance.

Meta-governance entails consideration of the mechanisms by which governments seek to control distal networks and hierarchies, such that those distal networks and hierarchies appear to be at ‘arms-length’ from government, but are actually much closer and much more embroiled in enacting government policy. Devolved parliaments and assemblies are an appositive example, and the notion of devolved business versus reserved business demonstrate meta-governance very clearly. In the English context, NHS England is an example of meta-governance in relation to the Department of Health (Hammond et al., 2019). Meta-governance refers to the ways that different modes of governance (across hierarchies, networks markets etc) are combined by government to ‘ensure the compatibility of different governance mechanisms and regimes,’ (Jessop, 1997). Essentially, the study of meta-governance equates to the study of examining how ‘control mechanisms are employed to enforce the rules of the game’. In the context of the argument I develop here, the rules of the game are continued dominance of Westminster politics over the devolved jurisdictions. This has been affected through a meta-governance strategy, which has refused to define the English policy context. In this context, meta-governance might be shown to operate whereby the central parliament seeks to control the policies of the devolved parliament through the application of reserved parliamentary business and where the regional assemblies and parliaments operate at arms-length from Westminster, on devolved business. Up until COVID-19 pandemic conditions, this meta-governance frame could be said to be largely successful.

This meta-governance frame operated by preventing alliances between the jurisdictions by effectively operating on a principle of ‘divide and conquer’ whereby the dominant regime separated the population into particular communities or groups (i.e. the three other jurisdictions). The subsequent individual operation of these different groups then prevents the articulation of demands and identities across those groups into a generalised challenge to the dominant regime (Glynos and Howarth, 2008). What has happened in relation to the COVID pandemic has created a range of political contexts and events whereby English policy has been made visible in ways that have not previously been the case, and this, in turn, has enabled the three other jurisdictions to much more directly and explicitly develop and implement their policy through and against the dominant English centre.

5. Summary and conclusion

There are clear policy differences within and between the four jurisdictions. Within case differences relate to the characterisation of the relations between voluntary action and a range of stakeholders. There is congruence between Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland in terms of how the social value of voluntary action is both defined and operationalised in terms of the implementation of voluntary action policy. There is congruence in terms of the need to ensure diversity of access and opportunity across these jurisdictions. There is divergence in terms of questions around the role of the state, and the relationships between the state and voluntary action (this merits further consideration in terms of future analyses), with a suggestion that the Scottish government sees a role for the state as opportunity broker rather than opportunity provider.

The between cases analysis suggests a wider range of issues around English exceptionalism, and meta-governance, which would speak centrally and crucially to questions around the state of the union and the potentially significant and fundamental impact of the pandemic on the ongoing sustainability of that union. The analysis contained herein demonstrates that there is a clear divergence across the four jurisdictions in terms of the different ‘frames of sense making’ utilised to constitute the field of voluntary action. The next stage of the analysis will seek to codify and extrapolate these differences across a much wider range of policy documents, collected before and during the UK response to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

6. References

Cabinet Office (2010a) Building a stronger civil society: a strategy for voluntary and community groups, charities and social enterprises. Cabinet Office. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/78927/building-stronger-civil-society.pdf (Accessed: 11 March 2021).

Cabinet Office (2010b) The Coalition: our programme for government. Cabinet Office. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-coalition-our-programme-for-government (Accessed: 11 March 2021).

De Cleen, B., Glynos, J. and Mondon, A. (2018) Critical research on populism: Nine rules of engagement, Organization, 25(5), pp. 649–661. doi: 10.1177/1350508418768053.

Department of Social Development Northern Ireland (2012) Join in, Get involved: Build a better future. The volunteering strategy for Northern Ireland. Department of Social Development Northern Ireland. Available at: https://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/publications/join-get-involved-build-better-future (Accessed: 22 February 2021).

Dowling, E. and Harvie, D. (2014) Harnessing the Social: State, Crisis and (Big) Society, Sociology, 48(5), pp. 869–886. doi: 10.1177/0038038514539060.

Glynos, J. and Howarth, D. (2007) Logics of critical explanation in social and political theory. Routledge.

Glynos, J., Speed, E. and West, K. (2014) Logics of marginalisation in health and social care reform: Integration, choice, and provider-blind provision, Critical Social Policy, 35(1), pp. 45–68. doi: 10.1177/0261018314545599.

Hammond, J. et al. (2019) Autonomy, accountability, and ambiguity in arm’s-length meta-governance: the case of NHS England, Public Management Review, 21(8), pp. 1148–1169. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2018.1544660.

Howarth, D. (2000) Discourse: Concepts in the social sciences. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Jessop, B. (1997) Capitalism and its future: remarks on regulation, government and governance, Review of International Political Economy, 4(3), pp. 561–581. doi: 10.1080/096922997347751.

Kruger, D. (2020) ‘Levelling Up Our Communities’. Available at: https://www.dannykruger.org.uk/sites/www.dannykruger.org.uk/files/2020-09/Kruger%202.0%20Levelling%20Up%20Our%20Communities.pdf (Accessed: 21 March 2021).

Scottish Government (2019) Volunteering for All: national framework. Scottish Government. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/volunteering-national-framework/ (Accessed: 22 February 2021).

Welsh Government (2015) Volunteering policy: Supporting communities, changing lives. Welsh Government. Available at: https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-01/volunteering-policy-supporting-communities-changing-lives.pdf (Accessed: 22 February 2021).

Woodhouse, J. (2015) ‘The voluntary sector and the Big Society’. House of Commons Library. Available at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN05883/SN05883.pdf (Accessed: 11 March 2021).

Yeandle, S. (2016) ‘From Provider to Enabler of Care? Reconfiguring Local Authority Support for Older People and Carers in Leeds, 2008 to 2013’, Journal of Social Service Research, 42(2), pp. 218–232. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2015.1129015.

[i] For example, consider the case of the health service. There is no longer a national health service which covers the whole of the UK. Health care in England is co-ordinated between the Department of Health and Social Care, (which is a UK government department with statutory responsibilities), and NHS England, which is a non-departmental specific public body which operates at arms-length from government and has oversight of the NHS in England. This is a fundamentally different structure to how healthcare is organised in Scotland.

Click here to download the PDF version of the working paper